One of the most persistent myths about the shillelagh is that it was simply a walking cane. Nothing more than a walking aid like the kind an elderly gentleman might lean on while strolling through the countryside. And while it’s true that a shillelagh could function perfectly well as a walking stick, reducing it to just that erases centuries of history and overlooks the deeper purpose behind its design, construction, and daily use.

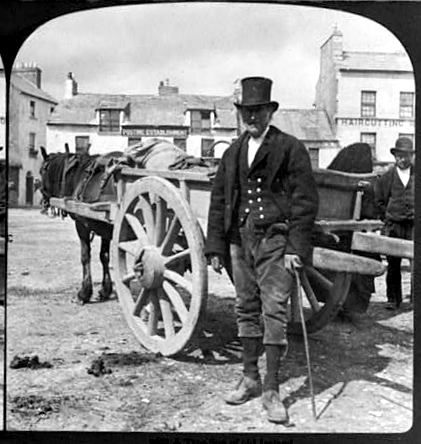

To understand why this myth is inaccurate, you have to picture life in rural Ireland before the twentieth century. Roads were unpaved, travel was unpredictable, and violence was far more common in areas where law enforcement was minimal or nonexistent. A shillelagh offered stability on rough terrain, but it also provided a means of defense. It served the same dual-purpose role as a shepherd’s staff or a self-defense tool. Something ordinary and practical for everyday tasks but deadly in the hands of someone trained.

The myth likely spread because using a stick as a walking cane made it socially acceptable to carry. If someone asked why an Irishman carried a sturdy hardwood club everywhere he went, he could simply shrug and say it was for walking. That explanation covered a multitude of situations and kept authorities or rivals from questioning his intentions. In this sense, the shillelagh’s identity as a walking cane wasn’t a limitation, it was actually a clever disguise.

Dig a little deeper into history, though, and the martial purpose of the shillelagh becomes impossible to ignore. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Ireland experienced a phenomenon known as faction fighting, where groups or families would engage in organized combat using sticks and sometimes stones. These weren’t mere bar fights, they were coordinated events with rules, rivalries, and massive participation. The shillelagh played a central role, with fighters employing real techniques that involved strikes, blocks, binds, footwork, and deceptive movements.

The idea that such a highly refined martial tradition developed around a “walking cane” simply doesn’t hold up. The shillelagh was engineered for durability and combat efficiency. It was cut from dense woods like blackthorn or oak, cured for months or years, and hardened using smoke or fire. The root knob of the plant was often shaped into a natural striking surface capable of dealing significant damage when used by a skilled practitioner. None of this craftsmanship suggests that the shillelagh was built solely for leaning on during long walks.

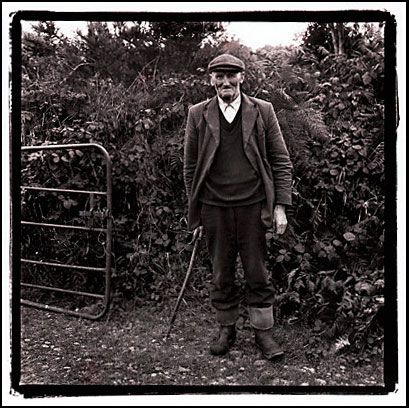

Modern practitioners understand this distinction well. For example, in the Combat Shillelagh system, students quickly learn the difference between a shillelagh used for mobility and one constructed for training or self-defense. While a shillelagh can absolutely function as a cane, and many practitioners love carrying it that way. The real magic happens when you learn to use it as a dynamic martial tool. The grips, angles, guards, and footwork taught in Combat Shillelagh bring out the weapon’s full potential, revealing just how far removed the martial art is from simple cane use.

Even in contemporary practice, people enjoy the dual-purpose nature of the shillelagh. It remains legal to carry almost everywhere specifically because it can be classified as a walking stick, yet practitioners know they are carrying something far more meaningful and capable. This blend of practicality and martial utility is part of the charm. It’s what allowed the shillelagh to survive through restrictive eras in Irish history and what makes it so appealing to practitioners today.

So, while the shillelagh can be used as a walking cane, calling it “only” that misses the point entirely. It is a versatile, historical, and highly effective martial instrument. Its identity as a cane was not its limitation, it was its cover story.